Charles Gaines

Numbers and Trees, X1, #3, Audrey, 2014

acrylic sheet, acrylic paint, ink, foamboard

46 1/2 x 50 1/4 x 3 1/2 inches

Clarissa Tossin

Shared Napkin (Andrezza, Guilherme, Ludovic, and I), 2007

paper napkin, lipstick, grease, red wine, chocolate, tomato sauce, and coffee

11 1/2 x 16 1/4 inches

Clarissa Tossin

Shared Napkin (Louisa, Lindsay, and I), 2007

paper napkin and pomegranate

9 1/2 x 9 1/2 inches

Alise Spinella

I Hold the Line, 2014

charcoal, grease pencil, graphite, acrylic polymer on canvas

36 x 28 inches

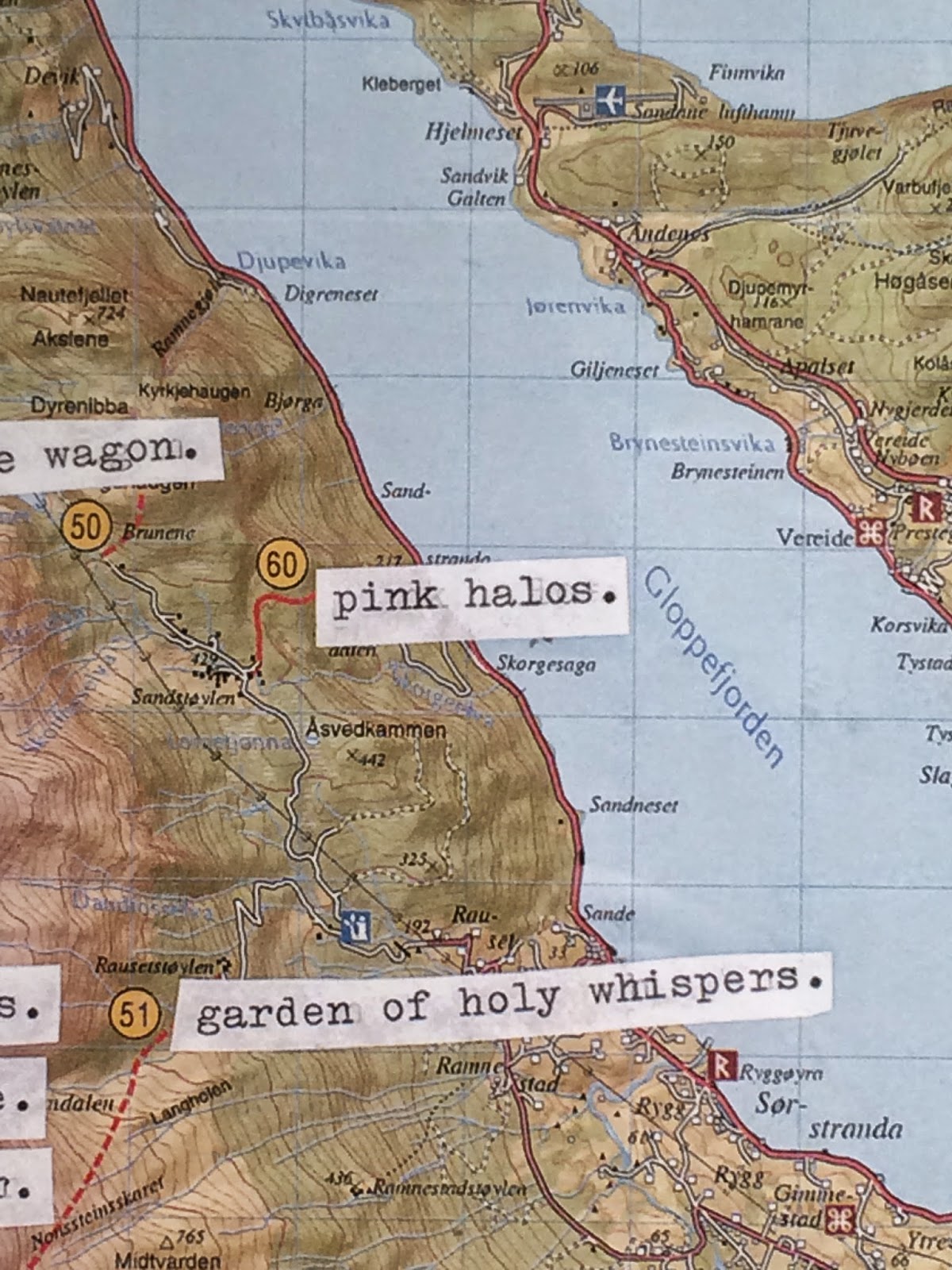

Steve Roden

Gloppen = Open Glow, 2007

Four-color offset printed map

27 x 39 inches

The map, a representation of a surface largely uneven and virtually incomprehensible at any scale, charts a landscape, a body, a relation of parts. Seeing these works had me thinking about Vermeer's paintings that included maps in their backgrounds thereby suggesting a way to look at painting as map but also to think about a subject of exploration, one of great unknowns in Vermeer's time since so few had developed any sense of a world-image, certainly as we know it today from satellite photos and daily, global exchange. So, this show had me wondering, ultimately, how I was to think about the map-maker, the cartographer (the artist I'm assuming) rather than the the map as subject.